Flood Plain Forest

-

About

What is the Randolph Flood Plain Forest?

Located in the town of Randolph, between the Third Branch of the White River, Prince St, Pleasant St, and Randolph Ave, the Randolph Floodplain Forest is one of Vermont’s largest remaining Sugar Maple-Ostrich Fern Riverine Flood Plain Forests (one of the rarer floodplain forest types). Flood Plains are periodically inundated by heavy rains and spring thaws. Their porous nature allows them to absorb considerable amounts of water before reaching flood stage. They thus act as protective sponges helping to reduce the effects of flood events. It is therefore in the town's best interest to protect and maintain this rare gem.

How is RACDC involved?

RACDC owns about 15+ acres of the Randolph Floodplain Forest. One of the greatest threats to the floodplain forest is invasive plant species. RACDC is therefore working with several partners to preserve the natural integrity of the forest for recreation, nature study, and use as an outdoor classroom. If you would like to volunteer in this effort please contact us by filling out the volunteer form or calling the office.

-

Native Species

-

Forest Flora

Forest Flora

While there is a single natural community on the property (Sugar Maple-Ostrich Fern Riverine Floodplain Forest), there are two distinct forest types present. The two areas appear to have different land-use histories as evidenced by their different species composition, and a partial row of stone fence posts that roughly separates them.

Forest Type 1

The canopy of this forest type is white pine, eastern hemlock, and northern hardwoods. This forest type is typical of a late stage of succession, which indicates that the land may have been cleared of trees more recently than in Forest Type 2. The wide canopy of the white pine trees is evidence that there were few trees surrounding them throughout much of their early years of growth. The understory is predominantly exotic shrub honeysuckle, wild grape, trout lily, and bloodroot, and dwarf scouring rush in the most heavily shaded spots. Zigzag goldenrod and elderberry are found in the forest openings.

Eastern White Pine

Eastern Hemlock

Forest Type 2

The canopy of this forest type is composed of northern hardwoods, mostly sugar maple. This forest type is typical of a final stage of succession, which indicates that the land may have been cleared of trees longer ago than in Forest Type 1. It was likely cleared for sheep grazing in the mid-1800s. The young American beech, whose dried leaves are the last to remain clinging to branches in winter, and sugar maple in the understory are tolerant of full shade, indicating that they will continue to dominate the canopy until disturbances create sunny openings which cottonwood, yellow poplar, American elm, big-tooth aspen, butternut, and black cherry trees prefer. The understory is currently composed of common scouring rush, ostrich fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris), lady fern (Athyrium filix-femina), Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides), and sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis), wild grape, and the exotic Japanese barberry and shrub honeysuckle. The generally closed canopy gives less light for regeneration of shade-intolerant tree seedlings.

-

River Wildlife

River Wild Life

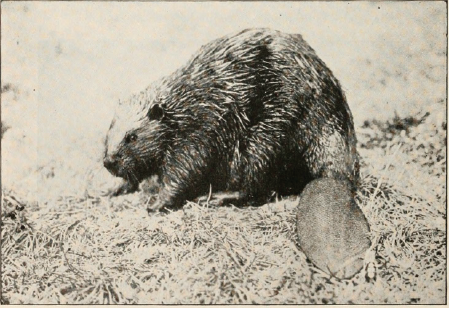

Beaver presence in this river is evident by teeth marks seen on trees near the river. Beavers are a keystone species that shaped the watersheds and aquatic ecosystems of North America for millions of years, slowing down floodwaters and allowing more water, silt, and nutrients to soak in for use by surrounding vegetation with their dams. Beaver-structured creeks yield perfect spawning grounds for many species of fish.

Photo: Ron Singer, USFWS

The river otter has occasionally been spotted in this river. It has a curious, playful nature. It eats fish, frogs, crayfish, snakes, turtles, amphibians, birds and small mammals. Mating takes place in March or April, and the young aren’t born until the following year. Young are only independent enough to leave their mother’s den after 3 or 4 months.

Birds such as Cliff Swallow (Left) and belted kingfisher (Center) nest in steep eroding banks. Egrets and herons (Right) tend to hunt perched on logs, grassy banks, and shallow, slow-moving or still water. Fish such as brown, rainbow, and brook trout, two species of suckers, several minnows, slimy sculpin, and many other aquatic species inhabit the river.

The slimy sculpin is native to Vermont. It has irregular dark brown or black blotches on a brown background and lacks scales. It prefers rocky, gravely, high gradient waters. It spawns in spring, is a bottom feeder that eats mostly insect larvae and nymphs, and is most active at night.

The brown trout is native to Europe and western Asia and was introduced in Vermont in the late 1800s. It’s brown or greenish with black spots that are sometimes surrounded by pale halos. Juveniles eat insects and adults eat small fish and crustaceans. Unlike most native trout, its spawning season is in the fall, which prevents its eggs from being trapped in ditches during irrigation season.

The rainbow trout is native to North American west coast waters and was introduced in Vermont in the 1800s. Its tail and sides have small black spots and a pink or reddish rainbow stripe. Juveniles eat insects and adults occasionally eat small fish and crustaceans. It generally prefers faster water than brook and brown trout and spawns mostly in the spring.

The brook trout is native to Vermont. Its most distinguishing feature is the small fin on its back directly in front of the tail. It tolerates a wider range of water pH levels than brown trout or rainbow trout, although it has a lower heat tolerance. Juveniles eat insects and adults occasionally eat small fish and crustaceans. It is more of a daytime feeder than brown or rainbow trout.

-

Vernal Pools

Vernal Pools

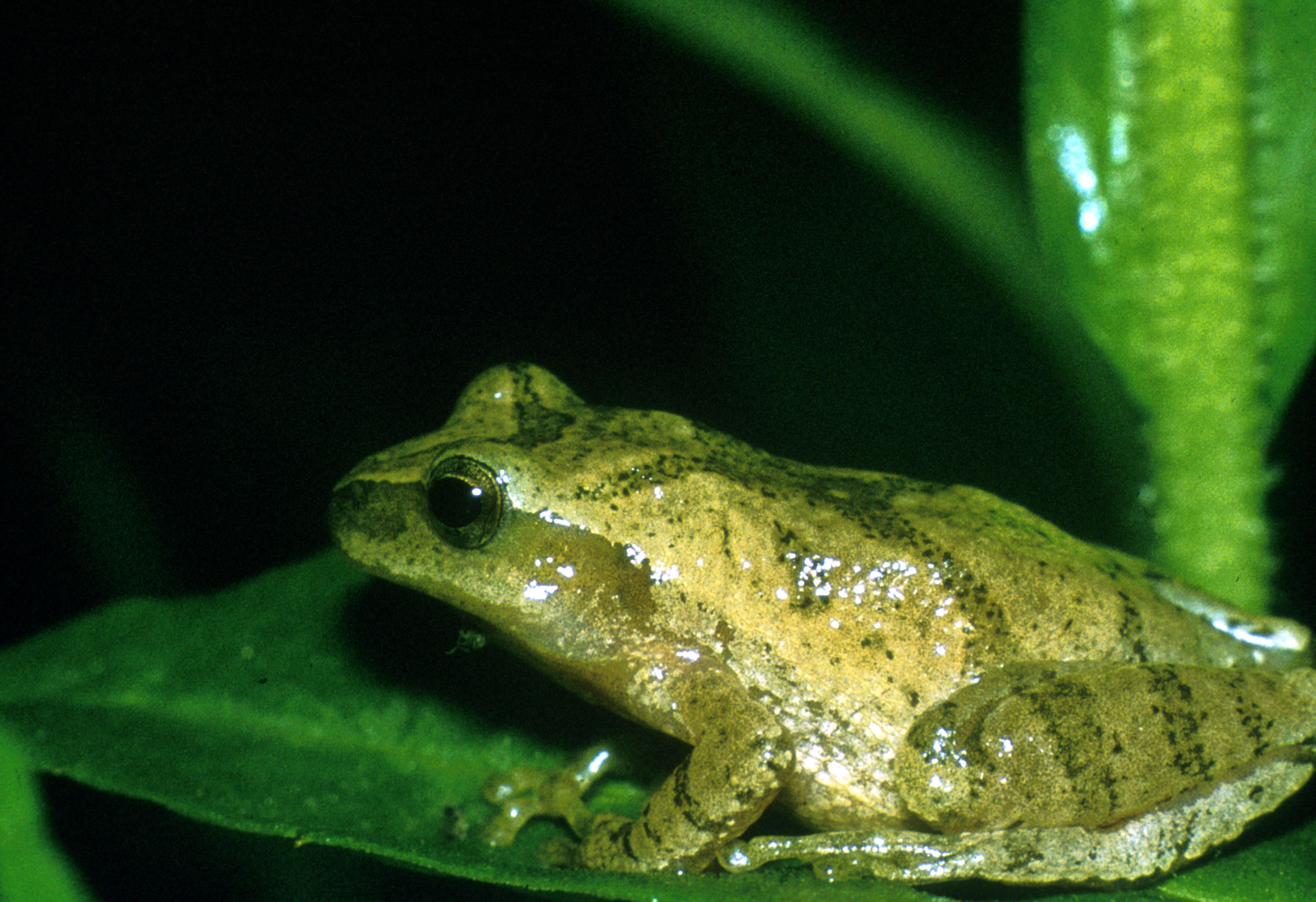

A vernal pool is a body of water in a depression or dip in the land lacking a permanent above-ground outlet. It contains water for only a few months in the spring and early summer with the rising water table of fall and winter or with the meltwater and runoff of winter and spring snow and rain. By late summer, most vernal pools are dry. A vernal pool, because of its periodic drying, does not support breeding populations of fish. Some species must use a vernal pool for part of their life cycle to avoid predation by fish, and their presence in a body of water indicates that it is a vernal pool. In New England, these obligate vernal pool species are the fairy shrimp, mole salamanders, and wood frogs. Gray tree frogs, American toads, and spring peepers also use vernal pools but are not obligate species because they don’t depend upon vernal pools for survival.

Photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Wood frogs are an amphibian species of upland forests. They travel to vernal pools in early spring, lay eggs, and return to the moist woodland for the rest of the year. The tadpoles develop in the pool and eventually follow the adults to nearby uplands.

Photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

The Spring Peeper is one of Vermont’s smallest frogs, generally up to 1-1½ inches long as an adult. They can be light to dark brown, have dark markings on their back that usually form an “X”, and small sticky discs on toes. their call can either be a short rising whistle or a series of rising peeps. The peak calling time is early May and can be heard into July. Breeding males have black throats and swollen thumbs. After mating, Spring Peepers lay hundreds of eggs singly or in packages of 2-3 eggs attached to vegetation. Tadpoles metamorphose within 2-3 months.

Photo: Greg Schechter

Spotted and Blue Spotted Salamanders are upland organisms. They spend most of their lives in burrows on the forest floor. Once a year on a rainy night, they migrate to ancestral vernal pools to mate and lay eggs, returning to the upland soon after. The eggs develop in the pool and young emerge to begin their life as a land-dwelling animal when the pool dries.

Fairy shrimp are small (about 1 inch) crustaceans which spend their entire lives (a few weeks) in a vernal pool. Eggs hatch in late winter/early spring and adults may be observed in pools in the spring. Females eventually drop an egg case which remains on the pool bottom after the pool dries. The eggs pass through a cycle of drying and freezing, and then hatch another year when water returns, so fairy shrimp may not be evident in some years.

-

Forest Flora

-

Invasive Species

-

Wild Chervil

Wild Chervil

Identification:

Wild Chervil has leaves that alternate and are twice divided that look similar to ferns. There is often a rosette of leaves surrounding main flower stalk. Chervil has hollow stems up to 6 feet tall covered with fine hair, and flowers white with a five notched petal, borne in compound umbels. Chervil flowers much earlier than native members of the carrot family such as Queen Anne's Lace.

Threat to the Floodplain Forest:

Wild Chervil spreads very rapidly, producing hundreds of seeds per plant each year. It leafs out very early in the spring, shading out native plants. People walking along the trails are most likely responsible for its spread into the interior of the forest.

-

Japanese Knotweed

Japanese Knotweed

Identification:

Japanese Knotweed leaves are broadly ovate-lanceolate and grow up to 6 inches long. Stems are hollow and bamboo-like, that grow up to 10 feet tall covered with scales, growing from rhizomes that can be 65 feet in length. Their flowers are greenish-white, borne in racemes at the top of the plant. The stalks and leaves turn brown and die back following the first frost.

Threat to the Floodplain Forest:

Knotweed is an aggressive invader, forming dense strands that spread through tough rhizomes. Knotweed is easily spread by water when small portions of the stem or roots break off and travel downstream. Regular flooding of the forest spreads Knotweed from the stands along the riverbank into the interior of the forest. The heavy shade created by Knotweed prevents native plants from germinating.

Photo: Anneli Salo

-

Reed Canary Grass

Reed Canary Grass

Identification:

Reed Canary Grass is a perennial grass that grows up to 6 feet in height. Their leaves gradually taper toward the tip and are solid green, changing from green to purplish to tan as the seeds mature. The grass produces panicles 3-10 inches long, first appearing as upright spikes then gradually opening.

Threat to the Floodplain Forest:

Reed Canary Grass spreads quickly through rhizomes, forming dense monocultures that inhibit the germination of native species and grow too thickly to provide habitat for birds or rodents. It grows very quickly in exposed soil and could become a problem along the riverbanks.

Photo: R. A. Nonenmacher

-

Autumn Olive

Autumn Olive

Identification:

Autumn Olive's leaves alternate and are lance-shaped. This plant is dark green above and silvery below. Their bark is grayish tan and often dotted with yellow resin dots. Autumn Olive can reach heights up to 20 feet tall. Their flowers are very fragrant and are light yellow, tubular, that grow along twigs. Autumn Olives produce red to pink juicy berries dotted with silvery scales.

Threat to the Floodplain Forest:

Autumn olive contains nitrogen-fixing root nodules allowing it to thrive in poor quality soils. It creates heavy shade which suppresses native herbaceous plants and inhibits seedling germination.

-

Common Buckthorn

Common Buckthorn

Identification:

Common Buckthorn leaves grow sub-opposite and are smooth dull green with several pairs of veins curling toward the tip, similar to dogwood. They have small thorns located where the branch splits and adjacent to terminal bud on each branch. Their twigs show prominently raised speckles and thorn-like spur branches. Common Buckthorn is a shrub or small tree that can grow 20 feet in height. Their flowers are greenish-yellow and have four petals that originate from axils to form flat or rounded top clusters. They produce fleshy blackberries.

Threat to the Floodplain Forest:

Buckthorn is most successful in areas with high light levels and exposed soil. Due to the hydrological regime of the floodplain forest, regular flooding of the White River promotes these conditions by exposing soil and depositing nutrients. Light levels along the river are relatively high due to the gap formed by the river.

Photo: Leslie J. Mehrhoff

-

Dames Rocket

Dames Rocket

Identification:

Dames Rocket has leaves that alternate and are hairy, oblong, sharply toothed increasing in size toward the base of the stem that grows 2-3 feet high. They flower large clusters of fragrant white, pink, or purple with four petals. They produce fruit oblong pod that splits down the middle that are 2-4 inches long producing hundreds of seeds.

Threat to the Floodplain Forest:

Dames rocket prefers moist to mesic woodlands and is capable of tolerating low light levels. Due to its ability to produce large amounts of seeds from each plant, it can quickly spread. It can easily be identified by the basal rosette in late fall and early spring. Because it is a biennial, yearly monitoring is necessary to ensure eradication.

-

Shrub Honeysuckle

Shrub Honeysuckle

Identification:

Shrub Honeysuckle has oblong egg shaped leaves that grow opposite to one another and are 1-5 inches long. They have tan to brown shreddy stems with a hollow pith. They can grow up to 15 feet high. The flowers are pink, red, yellow, or white with five petals that are tubular and grow in leaf axils. They produce red, juicy berries.

Threat to the Floodplain Forest:

Honeysuckles can tolerate moderate shade and can easily become established in soils that have been disturbed making the floodplain forest an ideal habitat for them. Because they leaf out earlier than most native species, Honeysuckles shade the ground below them, reducing the species diversity of native herbaceous plants.

Photo: Leslie J. Mehrhoff

-

Moneywort

Moneywort

Identification:

Moneywort is a herbaceous creeping plant that can form dense mats covering the ground. The leaves grow opposite and are round and small (0.5-1 inch). The flowers are about the same size as the leaves with five yellow petals with small red spots that emerge from the leaf axils, although Moneywort often doesn’t flower at all.

Threat to the Floodplain Forest:

Moneywort spreads quickly forming dense mats that inhibit germination of native vegetation.

Photo: Leslie J. Mehrhoff

-

Japenese Barberry

Japanese Barberry

Identification:

Japanese Barberry is a dome-shaped woody shrub that grows 3-6 feet in height. Their leaves are wedge-shaped growing in rosettes directly off branches. They have single thorns located just below leaves. The stems are tan on the outside and bright yellow inside the bark, that grow 6-9 feet. Flowers are yellow with six petals growing singly or in small upside down umbel from leaf axils.

Threat to the Floodplain Forest:

Japanese Barberry is very tolerant of low light levels and is capable of growing in a variety of soils. The high nitrogen content of its leaves can alter soil nitrogen levels. Its dense foliage shades out native herbaceous plants.

-

Wild Chervil

- Trails

-

Volunteer